Deep beneath the earth's surface, where sunlight never reaches and the air hangs thick with dust, a peculiar profession thrives on the razor's edge between life and commerce. These are the mine risk assessors – men and women who gamble with mortality to place a price tag on gemstones while they're still embedded in the very rock that could collapse and bury them alive.

The job doesn't appear in career guidance brochures. No university offers degrees in underground valuation. Yet in mining towns across South America, Africa, and Southeast Asia, these assessors form the critical link between desperate diggers and international gem markets. They descend into makeshift shafts where safety regulations are written in the dirt, armed only with a headlamp, a jeweler's loupe, and decades of hard-won instinct.

What makes their work extraordinary isn't just the danger – it's the impossible calculations they perform under pressure. A mistake in valuation doesn't mean corporate losses; it means angry miners realizing they've been cheated out of a fortune. Stories circulate of assessors who misjudged a sapphire's quality by one grade and disappeared into the jungle forever. The best practitioners develop a sixth sense for truth – both in stones and in the men who unearth them.

Morning rituals reveal the psychological toll. Seasoned assessors will tap their helmets three times before descent, a superstition born from counting colleagues who never surfaced. They chew coca leaves or local stimulants not for pleasure, but to sharpen their eyesight in the dim flicker of helmet lights. The underground markets have their own time zone – deals happen when the stones come out, whether that's 3 PM or 3 AM.

The assessment process itself resembles a high-stakes magic trick. An assessor might lick a rough emerald to see its true color beneath the dust. They'll breathe on rubies to check for heat conductivity that reveals synthetics. Some rub stones against their teeth, as enamel detects surface treatments better than any machine. These techniques were developed over generations, passed down through whispered conversations in mine tunnels where corporate spies might be listening.

Modern technology struggles to replace them. Laboratory gemologists with their spectrometers and refractometers might scoff at these "backward" methods, but no machine can navigate the social complexities of a mining camp. An assessor worth his salt knows which warlord controls which tunnel, which diggers spike their finds with glass implants, and which mines are about to be raided by government forces. This intelligence affects valuations as much as the stones themselves.

Their fee structure tells its own story. Most take percentage cuts rather than day rates – betting their livelihoods on each judgment call. In Tanzania's tanzanite mines, top assessors earn more than surgeons, yet still share communal toilets with miners. The money flows as unpredictably as the gem deposits; one month brings bankruptcy, the next buys a villa. Many develop telltale nervous tics from the constant adrenaline – eye twitches during negotiations or fingers that unconsciously trace escape routes.

The new generation faces unprecedented challenges. Synthetic gems now fool even experienced eyes, requiring assessors to carry portable UV lights and magnification tools. Climate change has made monsoons more violent, flooding mines mid-assessment. And smartphone cameras allow diggers to secretly photograph valuations for second opinions, destroying the assessor's informational advantage. Some veterans are teaching their children the trade, creating dynasties of risk. Others beg their offspring to take office jobs, knowing the profession's golden age has passed.

Perhaps the most haunting aspect is the assessors' own philosophy about their work. They don't see themselves as gamblers, but as translators between two incompatible worlds – converting geological chance into bankable certainty. When a tunnel collapses (as they frequently do), the first rescuers sent in are often rival assessors, not because of bravery, but because they can estimate the value of trapped miners' finds to determine if rescue costs are justified. Even salvation comes with a price tag.

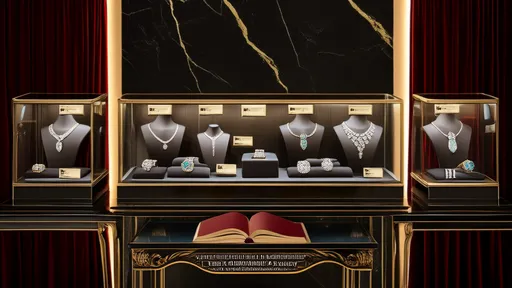

In an era where most valuations happen via spreadsheet in air-conditioned offices, these men and women remain the last human link in a chain that connects backbreaking labor to glittering jewelry stores. Their profession persists because some truths can't be measured by machines – only by those willing to stare into the earth's depths and emerge with stories written in stone and survival.

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025