In the quiet corners of the funeral industry, a little-known trade thrives in the shadows. Funeral jewelry recyclers operate in a gray zone, where sentimentality meets commerce, and ethics blur with opportunity. These individuals specialize in acquiring, repurposing, and reselling jewelry once meant to memorialize the dead—a practice that raises uncomfortable questions about ownership, grief, and the afterlife of personal artifacts.

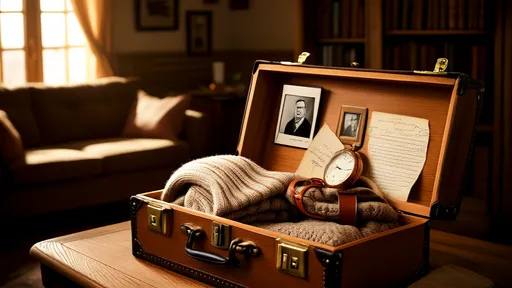

The business begins with the delicate task of sourcing materials. Funeral jewelry, often containing locks of hair, ashes, or inscribed dedications, finds its way into the secondary market through estate sales, pawnshops, and online auctions. Some pieces are surrendered by families who no longer wish to keep them; others are discreetly liquidated by heirs unaware of their emotional significance. The recyclers act as intermediaries, filtering these items into a niche but surprisingly active market.

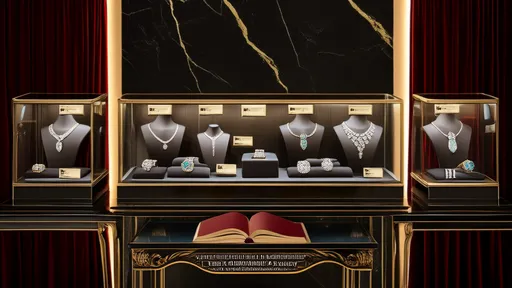

What makes this trade particularly controversial is its emotional weight. Unlike standard antiques or secondhand goods, funeral jewelry carries the invisible burden of loss. Victorian mourning rings, for instance, were crafted to honor specific individuals—their hair woven into intricate patterns beneath glass. Modern cremation pendants serve a similar purpose, holding minute quantities of ashes. When these objects change hands, they bring with them unresolved stories, leaving buyers to wonder about the lives (and deaths) they once represented.

The industry’s lack of regulation only deepens the ethical murkiness. No laws prohibit the resale of funeral jewelry, provided it isn’t stolen. Yet the absence of clear guidelines means transactions often hinge on trust—or the lack thereof. Some recyclers meticulously research each piece’s history, offering transparency to buyers. Others strip away identifying marks, erasing the past to make items more palatable to new owners. The line between preservation and exploitation grows thinner with each sale.

For collectors, the appeal is multifaceted. Some seek out mourning jewelry for its historical value, studying the evolving customs around death. Others are drawn to the craftsmanship, particularly in older pieces where human hair was painstakingly braided into floral designs. Then there are those who purchase these items for their perceived spiritual energy, believing the jewelry retains a connection to the deceased. Whatever the motivation, demand ensures a steady flow of transactions, even as the origins of many pieces remain obscured.

Behind the scenes, the logistics of recycling funeral jewelry reveal an unexpected sophistication. Specialists must assess materials—determining whether hair is real, if ashes are authentic, or if gemstones hold value beyond their sentimental context. Metals are melted down, settings repurposed, and engravings carefully removed or preserved based on market trends. The process walks a tightrope between respect and profitability, with each decision impacting how the dead are remembered—or forgotten.

The digital age has transformed the trade, expanding both its reach and its risks. Online platforms allow recyclers to connect with global buyers, but they also expose the industry to scrutiny. Social media debates flare over whether selling memorial items constitutes sacrilege or sensible recycling. Meanwhile, fraudulent listings proliferate—fake ashes, counterfeit Victorian pieces, and forged provenance documents muddying an already opaque marketplace. The anonymity of the internet makes it easier than ever to profit from grief without facing the moral consequences.

Perhaps the most haunting aspect of this industry is its reflection of how modern society handles mortality. As traditional mourning rituals fade, funeral jewelry becomes both artifact and commodity. The recyclers, whether viewed as pragmatic entrepreneurs or ghoulish opportunists, fill a vacuum created by our discomfort with death. Their trade forces a confrontation with uncomfortable truths about what we keep, what we discard, and what we’re willing to sell when memory becomes just another form of currency.

In the end, the funeral jewelry recycling business persists because it answers an unspoken demand. For every person horrified by the idea of wearing a stranger’s mourning brooch, another sees beauty in its history. The gray zone thrives precisely because grief resists simple categorization—and because death, as always, creates markets where the living least expect them.

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025

By /Jul 4, 2025